Hungarians of Transylvania

published by HUNSOR.se

Geographically, Transylvania lies in the Carpathian Basin. The Magyars (hungarians) invaded this part of Europe in the begining of the 9th century. During the centuries and after many wars, the Hungarian kings invited other ethnicities, such as the Saxons from Germany, to settle and fill the place of the decreased Hungarian population, and to replenish the land of Transylvania again. For several centuries the state administration was based on the alliance of the following three nations: the Hungarian nobles, the Szeklers, and the free peasants and tradesmen of the autonomous Saxon territories. Other groups, such as the Rumanians in historic books mentioned as Vlachs, came to Transylvania later. Their first groups are mentioned in chronicles dated the 13th century, quoting them as poor shepherds wandering with their flocks from Wallachia across the Carpathian Mountains to seek asylum and refuge in the Kingdom of Hungary. Later immigrated even more spurred by pressures from the advancing Ottoman occupation.

Facts:

Transylvania is a historical region of Hungary and a present geographical region of Rumania, in the central part of the country. It was a part of Kingdom of Hungary untill 1920. In fact, it was the very area where the seven Hungarian tribes arrived in 896 A.D. and settled in the sparsely inhabited land. At the time another Hungarian group, called the Székelys had already been there, since 400 A.D., as the leftover remnants of the Huns of Attila. At the end of World War I, as part of the Treaty of Trianon, 1920, the Allies annexed Transylvania from Hungary to Rumania (to whom Transylvania had never belonged before). As a result of annexation to Rumania more than 2 million hungarians become minority in their own country.

Transylvania had been the integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary since 1000 a.d. until 1920 a.d. At the end of World War I, as part of the Treaty of Trianon, 1920, the Allies annexed Transylvania from Hungary to Rumania, however, the region remains a treasury of the one-thousand-year old Hungarian culture and modern Rumanian. Transylvania was first referred to in a Medieval Latin document in 1075 as ultra silvam, meaning "beyond the forest" (ultra (+accusative) meaning "beyond" or "on the far side of" and the accusative accusative case of sylva (sylvam) meaning "wood or forest"). Transylvania, with an alternative Latin prepositional prefix, means "on the other side of the woods".

Introduction - the early history

In its early history, the territory of Transylvania belonged to a variety of empires and states, including the Roman Empire, the Hun Empire and the Gepid Kingdom. There were also periods when autonomus political entities arose under the control of the Byzantine and the Bulgarian Empire. After 106 AD the Roman Empire conquered the territory and its wealth was systematically exploited. After the Romans' withdrawal in 271 AD, it was subject to various temporary influences and migrations, and areas of it were under the control of peoples such as the Visigoths, Gepids and Avars. The area was again repopulated by Huns led by Attila in 400 AD and with them even Szekély-hungarians settled who even nowdays still live on their ancient territories. The Huns, built up a powerful empire under Attila but their Kingdom didn't last for long. After Hunnish rule faded, the Germanic Ostrogoths then the Lombards came to Pannonia, and the Gepids had a presence in the eastern part of the Carpathian Basin for about 100 years. In the 560s the Avars founded the Avar Khaganate, a state which maintained supremacy in the region for more than two centuries and had the military power to launch attacks against all its neighbours. The Avar Khagnate was weakened by constant wars and outside pressure and the Franks under Charlemagne managed to defeat the Avars ending their 250-year rule. Neither the Franks nor others were able to create a lasting state in the region until the freshly unified Hungarians led by Árpád settled in the Carpathian Basin starting in 896.

![[Pannonia before the Magyars

]](Carpathianbasin_9th_pici.jpg)

Pannonia before the Magyars

Establishing Hungary (896–1000)

At the end of the 9th century the Magyars conquered the area and firmly established their control over it in 896 AD. [See "Magyar Conquest of Hungary"]. From the 9th/10th/11th century untill 1526, Transylvania was an integral part inside of the Kingdom of Hungary, led by a voivod appointed by the Hungarian King.

Hungary is one of the oldest countries in Europe. It was settled in 896, before France and Germany became separate entities, and before the unification of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Medieval Hungary controlled more territory than medieval France, and the population of medieval Hungary was the third largest of any country in Europe. Árpád was the Magyar leader whom sources name as the single leader who unified the Magyar tribes via the Covenant of Blood (Hungarian: Vérszerzodés) forged one nation, thereafter known as the Hungarian nation and led the new nation to the territory of the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century. After an early Hungarian state was formed in this territory military power of the nation allowed the Hungarians to conduct a lot of successful fierce campaigns and raids as far as today's Spain. A later defeat at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 signaled an end to raids on foreign territories, and links between the tribes weakened. The ruling prince (fejedelem) Géza of the Árpád dynasty, who was the ruler of only some of the united territory, but the nominal overlord of all seven Magyar tribes, intended to integrate Hungary into Christian Western Europe, rebuilding the state according to the Western political and social model. He established a dynasty by naming his son Vajk (the later King Stephen I of Hungary) as his successor. This was contrary to the then dominant tradition of the succession of the eldest surviving member of the ruling family.

![[Hungary in the 11th century]](hungary_11th_cent_pici.jpg)

Hungary in the 11th century

During the centuries and after many wars, the Hungarian kings invited other ethnicities, such as the Saxons from Germany, to settle and fill the place of the decreased Hungarian population, and to replenish the land of Transylvania again. For several centuries the state administration was based on the alliance of the following three nations: the Hungarian nobles, the Szeklers, and the free peasants and tradesmen of the autonomous Saxon territories. Other groups, such as the Rumanians, - in historic books mentioned as Vlachs, came to Transylvania later. Their first groups are mentioned in chronicles dated the 13th century, quoting them as poor shepherds wandering with their flocks from Wallachia across the Carpathian Mountains to seek asylum and refuge in the Kingdom of Hungary.

The Patrimonial Kingdom (1000-1222)

Hungary was established as a Catholic Apostolic Kingdom under saint Stephen I.

Applying to Pope Sylvester II, Stephen received the insignia of royalty (including the still existent Holy Crown of Hungary) from the papacy. He was crowned in December 1000 AD in the capital, Esztergom. Papacy confers on him the right to have the cross carried before him, with full administrative authority over bishoprics and churches. He was the son of Géza and thus a descendant of Árpád. By 1006, Stephen had solidified his power, eliminating all rivals who either wanted to follow the old pagan traditions or wanted an alliance with the Eastern Christian Byzantine Empire. Then he started sweeping reforms to convert Hungary into a western feudal state, complete with forced Christianisation. Stephen established a network of 10 episcopal and 2 archiepiscopal sees,and ordered the buildup of monasteries churches and cathedrals. He followed the Frankish administrative model: The whole of this land was divided into counties (megyék), each under a royal official called an ispán count (latin: comes)—later foispán (latin : supremus comes). This official represented the king’s authority, administered its population, and collected the taxes that formed the national revenue. Each ispán maintained at his fortified headquarters (castrum or vár) an armed force of freemen.

What emerged was a strong kingdom that withstood attacks from German kings and Emperors, and nomadic tribes following the Hungarians from the East, integrating some of the latter into the population (along with Germans invited to Transylvania and the northern part of the kingdom, especially after the Battle of Mohi), and and subjugating Croatia in 1102 when Hungarian King Coloman is crowned king of Croatia.

Important members of the Árpád dynasty:

King Coloman the "Book-lover" (King: 1095-1116):

One of his most famous laws was half a millennium ahead of its time: De strigis vero quae non sunt, nulla amplius quaestio fiat (As for the matter of witches, no such things exist, therefore no further investigations or trials are to be held).

Béla III (King: 1172-1192):

was the most powerful and wealthiest member of the dynasty, Béla disposed of annual equivalent of 23,000 kg of pure silver. It exceeded those of the French king (estimated at some 17,000 kilograms) and was double the receipts of the English Crown. He rolled back the Byzantine potency in Balkan region.

Andrew II of Hungary (King: 1205-1235) :

In 1211, he granted the Burzenland (Transylvania) to the Teutonic Knights. In 1225, Andrew II expelled the Teutonic Knights from Transylvania, hence Teutonic Order had to transfer to the Baltic sea. He led the Fifth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1217. He set up the largest royal army in the history of crusades (20,000 knights and 12,000 castle-garrisons ). The Golden Bull of 1222 was the first constitution in Continental Europe. It limited the king's power. The golden Bull —the Hungarian equivalent of England’s Magna Carta—to which every Hungarian king thereafter had to swear. Its purpose was twofold: to reaffirm the rights of the smaller nobles of the old and new classes of royal servants (servientes regis) against both the crown and the magnates and to defend those of the whole nation against the crown by restricting the powers of the latter in certain fields and legalizing refusal to obey its unlawful/unconstitutional commands (the "ius resistendi"). The lesser nobles also began to present Andrew with grievances, a practice that evolved into the institution of the parliament, or Diet. The most important legal-ideology was the Doctrine of the Holy Crown.

![[Golden Bull of 1222]](aranybulla1.jpg)

The hungarian Golden Bull of 1222 was the first constitution in Continental Europe.

Age of elected Kings

Árpáds direct descendants in the male line ruled the country until 1301. During the reigns of the Kings after the Árpád dynasty, the Kingdom of Hungary reached its greatest extent, yet royal power was weakened as the major landlords (the Barons) greatly increased their influence. The most powerful landlords started to use royal prerogatives (coinage ,customs, declaration of wars against foreign monarchs). After the destructive period of interregnum (1301–1308), the first Angevin king, Charles I of Hungary (King: 1308-1342) -a descendant of the Árpád dynasty on the female line- successfully restored the royal power, who defeated oligarch rivals, the so called "little kings". New fiscal and monetary policies proved successful under his reign. One of the primary sources of his power was the wealth derived from the gold mines of Transylvania and north Hungary (modern Slovakia). Eventually production reached the remarkable figure of 3,000 lb. of gold annually - one third of the total production of the world as then known, and five times as much as that of any other European state. Charles also sealed an alliance with the Polish king Casimir.

The second Hungarian king in the Angevin line, Louis I the Great (1342–1382) extended his rule over territories to the Adriatic Sea, and occupied the Kingdom of Naples several times. He had become popular in Poland due to his campaign against the Tatars and pagan Lithuanians. Two successful wars (1357–58, 1378–81) against Venice annexed Dalmatia and Ragusa and more territories at Adriatic Sea. Venice also had to raise the Angevin flag on St. Mark's Square on holy days. Louis I established a university in Pécs in 1367 (by papal accordance). The Ottoman Turks confronted the country ever more often. In 1366 and 1377, Louis led successful champaigns against the Ottomans (Batlle at Nicapoli in 1366), therefore Balkanian states became his vassals. From 1370, the death of Casimir III of Poland, he was also king of Poland. Until his death , he retained his strong potency in political life of Italian Peninsula.

King Louis died without a male successor, and the country was stabilized only after years of anarchy when Sigismund (king: 1387-1437) a prince from the Luxembourg line succeeded to the throne by marrying Louis's daughter, Queen Mary. It was not for entirely selfless reasons that one of the leagues of barons helped him to power: Sigismund had to pay for the support of the lords by transferring a sizeable part of the royal properties. (For some years, the baron's council governed the country in the name of the Holy Crown ) The restoration of the authority of the central administration took decades of work. In 1404 Sigismund introduced the Placetum Regium. According to this decree, Papal bulls and messages could not be pronounced in Hungary without the consent of the king. Sigismund congregated Council of Constance (1414-1418) to abolish the Papal Schism of Catholic church, which was solved by the election of a new pope. In 1433 he even became Holy Roman Emperor.

In 1446, the parliament elected the great general John (János) Hunyadi as governor (1446–53) and then as regent (1453–56) of the kingdom. Hunyadi was a successful crusader against the Ottoman Turks, one of his greatest victories being the Siege of Belgrade in 1456. Hunyadi defended the city against the onslaught of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. During the siege, Pope Callixtus III ordered the bells of every church to be rung every day at noon, as a call for believers to pray for the defenders of the city. However, in many countries (like England and Spanish kingdoms), news of the victory arrived before the order, and the ringing of the church bells at noon thus transformed into a commemoration of the victory. The Popes didn't withdraw the order, and Catholic churches still ring the noon bell to this day.

The battle of Nándorfehérvár (today's Belgrade)

In 1456, three years after he captured Constantinople, Sultan Mohammed II encamped and set off to besiege Nándorfehérvár (today's Belgrade), hungary´s last and strongest defence fortress on south against turkish attacks. Serbia has been already occupied by the turkish army.

The Hungarian army was led by the hungarian king János Hunyadi. In that decisive battle Hungarians gained a decisive victory. This triumph at Nándorfehérvár turned back for nearly a century the Ottoman expansion threatening Europe. In Christian churches throughout the world, the pealing of the bells at noon still reminds people of the victory János Hunyadi achieved on July 22, 1456. Years that came were full of uprisings of different kinds (peasants, miners) within the kingdom. The country was weaker and weaker as time passed by. Is it any wonder that, after all this, there was not enough money for the war against the Turks, even legendary Nándorfehérvár fell in 1521.

Age of early absolutism

The last strong king was the Renaissance king Matthias Corvinus (king 1458–1490). Matthias was the son of John Hunyadi. Hungary was the first non-Italian country, where the renaissance appeared in Europe. András Hess set up a printing press in Buda in 1472.

A true Renaissance prince, a successful military leader and administrator, an outstanding linguist, a learned astrologer, and an enlightened patron of the arts and learning. Although Matyas regularly convened the Diet and expanded the lesser nobles' powers in the counties, he exercised absolute rule over Hungary by means of huge secular bureaucracy. Matthias set out to build a great empire, expanding southward and northwest, while he also implemented internal reforms. Like his father, Matthias desired to strengthen the Kingdom of Hungary to the point where it became the foremost regional power and overlord, strong enough to push back the Ottomans; toward that end he deemed necessary the conquering of large parts of the Holy Roman Empire.

His mercenary standing army called the Black Army of Hungary (Hungarian: Fekete Sereg) was an unusually big army in its age, it accomplished a series of victories also capturing parts of Austria, Vienna (1485) and parts of Bohemia. The king died without a legal successor. His library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe's greatest collection of historical chronicles, philosophic and scientific works in the 15th century, and second only in size to the Vatican Library which mainly contained religious material. His renaissance library is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Decline of Hungary (1490–1526)

The magnates, who did not want another heavy-handed king, procured the accession of Vladislaus II, king of Bohemia (Ulászló II in Hungarian history), precisely because of his notorious weakness: he was known as King Dobže, or Dobzse (meaning “Good” or, loosely, “OK”), from his habit of accepting with that word every paper laid before him. He squandered/(or signed away) rashly Matthias' huge property. The central power became insolvent.

In 1514, the weakened King Vladislaus II faced a major peasant rebellion led by György Dózsa, which was crushed barbarously by the nobles mainly by János Szapolyai. As central rule degenerated, the stage was set for a defeat at the hands of the Ottoman Empire. In 1521, the strongest Hungarian fortress in the South Nándorfehérvár (modern Belgrade) fell to the Turks, and in 1526, the Hungarian army was destroyed in the Battle of Mohács. The early appearance of protestantism further worsened the relations in the anarchical country.

Through the centuries the Kingdom of Hungary kept its old "constitution", which granted special "freedoms" or rights to the nobility and groups like the Saxons or the Jassic people, and to free royal towns such as Buda, Kassa (Košice), Pozsony (Bratislava), Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca)etc..

![[Hungary in the 17th century]](hungary_1683.png)

Hungary in the 17th century

The Age of Ottoman Turkish power in Central Europe (1526 - 1687)

After some 150 years of war in the south of Hungary, Ottoman forces conquered parts of the country, continuing their expansion until 1556. The Ottomans achieved their first decisive victory over the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohács in 1526.

In 1541, due to the Ottoman Turkish power in Central Europe, the Hungarian kingdom disintegrated into three parts. Between 1542 and 1688 Transylvania was a relatively independent principality, keeping its ties with Hungary. It paid tribute but was free from Turkish occupation. Between 1591 and 1606 civil wars between rival dukes destroyed Transylvania's unity. Later, Duke Gabor Bethlen (1613-1629) reestablished the stability and order in Transylvania.

Subsequent decades were characterised by political chaos. A divided Hungarian nobility elected two kings simultaneously, Hungarian-German origin 'Szapolyai János' (1526-1540) and Austrian Ferdinand Habsburg (1527-1540). Armed conflicts between the rival monarchs further weakened the country internally. With the conquest of Buda in 1541 by the Turks, Hungary was riven into three parts. The north-west (present-day Slovakia, western Transdanubia, present-day Burgenland, western Croatia and parts of north-eastern present-day Hungary) remained under Habsburg rule and although initially independent, it became a province of Austrian Empire under the informal name Royal Hungary. The Habsburg Emperors would from then on be crowned also as Kings of Hungary.

Principality of Transylvania (1571–1711)

The Principality of Transylvania was a semi-independent state ruled by mostly Calvinist Hungarian princes. The Principality existed as a semi-independent state from 1571 to 1711 and as part of the Habsburg Monarchy / Austrian Empire from 1711 to 1867.

The eastern part of the kingdom (Partium and Transylvania) became at first an independent principality, but gradually was brought under Turkish rule as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The remaining central area (most of present-day Hungary), including the capital of Buda, became a province of the Ottoman Empire. Much of the land was devastated by recurrent warfare. Most small settlements disappeared. Rural people living in the now Ottoman provinces could survive only in larger settlements known as Khaz towns, which were owned and protected directly by the Sultan. The Turks were indifferent to the sect of Christianity practiced by their Hungarian subjects. For this reason, a majority of Hungarians living under Ottoman rule became Protestant (largely Calvinist), as Habsburg counter-reformation efforts could not penetrate Ottoman lands. Hungary entered the Thirty Years' War, Royal (Habsburg) Hungary joined the catholic side, until Transylvania joined the protestant side.

![[Eastern Hungarian Kingdom 1550 which later became the Principality of Transylvania]](eastern_hungarian_kingdom1550.jpg)

Eastern Hungarian Kingdom 1550 which later became the Principality of Transylvania

On 29 August 1526, the army of Sultan Suleiman of the Ottoman Empire inflicted a decisive defeat on the Hungarian forces at Mohács. János Szapolyai (Zápolya) was en route to the battlefield with his sizable army but did not participate in the battle for unknown reasons. The youthful King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia fell in battle, as did many of his soldiers. As Szapolyai was elected king of Hungary, Ferdinand from the House of Habsburg also claimed the throne of Hungary. In the ensuing struggle Szapolyai received the support of Sultan Suleiman I, who after his death in 1540 occupied Buda and central Hungary in 1541 under the pretext of protecting Zápolya's son, John II. Hungary was now divided into three sections: the West and north Royal Hungary, Ottoman Hungary, and the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom under Ottoman suzerainty, which later became the Principality of Transylvania where Austrian and Turkish influences vied for supremacy for nearly two centuries. The Hungarian magnates of Transylvania resorted to policy of duplicity in order to preserve independence.

Transylvania was now beyond the reach of Catholic religious authority, allowing Lutheran and Calvinist preaching to flourish. In 1563, Giorgio Blandrata was appointed as court physician, and his radical religious ideas increasingly influenced both the young king John II and the Calvinist bishop Francis David, eventually converting both to the Anti-Trinitarian (Unitarian) creed. In a formal public disputation, Francis David prevailed over the Calvinist Peter Melius; resulting in 1568 in the formal adoption of individual freedom of religious expression under the Edict of Turda (the first such legal guarantee of religious freedom in Christian Europe, however only for Lutherans, Calvinists, Unitarians and of course Catholics, with the Orthodox Christian confession being explicitly banned).

The Báthory family, which came to power on the death of John II in 1571, ruled Transylvania as princes under the Ottomans, and briefly under Habsburg suzerainty, until 1602. Their rise to power marked the beginning of the Principality of Transylvania as a semi-independent state.

The younger István Báthory, a Hungarian Catholic who later became King under the name Stephen Bathory of Poland, undertook to maintain the religious liberty granted by the Edict of Turda, but interpreted this obligation in an increasingly restricted sense. The latter period of Báthory rule saw Transylvania under Zsigmond Báthory enter the Long War, which started as a Christian alliance against the Turks and became a four-sided conflict involving Transylvania, the Habsburgs, the Ottomans, and the voivod of Wallachia, Michael the Brave. Michael gained control of Transylvania in 1599 by defeating Andrew Báthory's army at the Battle of Selimbar, and became Prince of Transylvania, after his election by the Transylvanian nobles reunited in Diet. His rule was short lived, as Rudolf I's general Basta, ordered his assassination (which took place on August 9, 1601).

Around 1601 the Principality for a short time was under the rule of Rudolf I who initiated the Germanization of the population, and in order to reclaim the Principality for Catholicism the Counter Reformation. From 1604-1606, the Hungarian nobleman István Bocskay led a successful rebellion against Austrian rule. Bocskay was elected Prince of Transylvania on 5 April 1603 and prince of Hungary two months later. He achieved the Piece of Vienna in 1606)(June 23, 1606). By the Peace of Vienna, Bocskay obtained religious liberty and political autonomy, the restoration of all confiscated estates, the repeal of all "unrighteous" judgments, and a complete retroactive amnesty for all Hungarians in Royal Hungary, as well as his own recognition as independent sovereign prince of an enlarged Principality of Transylvania.

Under Bocskay's successors Transylvania had its golden age, especially under the reigns of Gábor Bethlen and György I Rákóczi. Gábor Bethlen, who reigned from 1613 to 1629, perpetually thwarted all efforts of the emperor to oppress or circumvent his subjects, and won reputation abroad by championing the Protestant cause. Three times he waged war on the emperor, twice he was proclaimed King of Hungary, and by the Peace of Nikolsburg (December 31, 1621) he obtained for the Protestants a confirmation of the Treaty of Vienna, and for himself seven additional counties in northern Hungary. Bethlen's successor, George I Rákóczi, was equally successful. His principal achievement was the Peace of Linz (September 16, 1645), the last political triumph of Hungarian Protestantism, in which the emperor was forced to confirm again the articles of the Peace of Vienna. Gabriel Bethlen and George I Rákóczi also did much for education and culture, and their era has justly been called the golden era of Transylvania. They lavished money on the embellishment of their capital Gyulafehérvár, which became the main bulwark of Protestantism in Eastern Europe. During their reign Transylvania was also one of the few European countries where Roman Catholics, Calvinists, Lutherans, and Unitarians lived in mutual tolerance, all of them belonging to the officially accepted religions - religiones recaepte, while the Orthodox, however, were only tolerated.

The fall of Várad (1660) marked the decline of the Principality of Transylvania which ended with the Habsburg monarchs gaining increased control of this territory. Under Prince Kemeny, the diet of Transylvania proclaimed the secession of Transylvania from the Ottomans (April 1661) and appealed for help to Vienna but a secret Habsburg-Ottoman agreement resulted in further increasing Habsburg influence.

Early modern times (1687 - 1718)

In 1687, after defeating the Turks, the Habsburgs made Transylvania into an Austrian crown colony (1688-1867). Although the Habsburg rule contributed to the development of western culture in Transylvania, it also limited the rights of the different nationalities living in Transylvania, especially that of the Hungarians and Saxons. The reduction of the Hungarians' national rights lead to the revolt of the Kuruces under the leadership of Duke Ferenc Rakoczi II (1703-1711). The goal was national independence. The unresolved tensions lead to the armed revolution of 1848-1849. During this revolution the Saxons, who wanted to defend their rights, and the Romanians, who sought national recognition, supported the Habsburgs against the Hungarian revolutionaries. In 1849 the Hungarian revolutionary government seceded from Austria, declared it´s independance as a souvereign state and the Transylvanian Diet declared the unification of Transylvania with Hungary.

In 1686, Christian forces led by the Habsburg army reconquered Buda, and in the next few years, all of the former Hungarian lands, except areas near Timisoara (Temesvár), were taken from the Turks. In the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz these territorial changes were officially recognized, and in 1718 the entire Kingdom of Hungary was removed from Ottoman rule.

Francis RákócziLargely throughout this time, Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava) acted as the capital (1536-1784), coronation town (1563-1830) and seat of the Diet of Hungary (1536-1848) . Nagyszombat in turn, acted as the religious center, beginning in 1541.

Concurrently, between 1604 and 1711, there was a series of anti-Austrian, and anti-Habsburg uprisings which took place in the Habsburg state of Royal Hungary (more precisely, in present-day Slovakia), as well as anti-Catholic uprisings, which were to be found across the Hungarian lands. Religious protesters demanded equal rights among Christian groups. The uprisings were usually organized from Transylvania.

This wave of rebellious movements ended with an uprising led by 'II. Rákóczi Ferenc', who was chosen by the people to be the future king. When the Austrians crushed the movement in 1711, Rákóczi had already escaped to Poland, and would live his final days in the nearby Ottoman town Rodosto. To make further armed resistance impossible, the Austrians destroyed several castles, most of those on the former borders between Royal Hungary and now-reclaimed Turkish territories. Peasants were allowed to dismantle many most of the remaining castles and recycle the stone as building materials (the végvárs among them).

Transylvania from (1849-1860)

With the help of Russian army units the Habsburg defeated this Hungarian revolution in blood, and after it executed a huge number of leading high hungarian officers. In the following period (1849-1860) Vienna suppressed all of Transylvania's nationalities, but mostly the hungarians, which were blamed ever after by the austrians for the revolution. Apart from the abolition of serfdom, none of the nations were pleased with the results of the revolution.

The divided country 1848 - 1867

After the revolution, the emperor revoked Hungary's constitution and assumed absolute control. Franz Joseph divided the country into four distinct territories: Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia-Slavonia, and Vojvodina. German and Bohemian administrators managed the government, and German became the language of administration and higher education. The non-Magyar minorities of Hungary received little for their support of Austria during the turmoil. A Croat reportedly told a Hungarian: "We received as a reward what the Magyars got as a punishment."

Hungarian public opinion split over the country's relations with Austria. Some Hungarians held out hope for full separation from Austria; others wanted an accommodation with the Habsburgs, provided that they respected Hungary's constitution and laws. Ferencz Deak became the main advocate for accommodation. Deak upheld the legality of the April Laws and argued that their amendment required the Hungarian Diet's consent. He also held that the dethronement of the Habsburgs was invalid. As long as Austria ruled absolutely, Deak argued, Hungarians should do no more than passively resist illegal demands.

The first crack in Franz Joseph's neo-absolutist rule developed in 1859, when the forces of Sardinia and France defeated Austria at Solferno. The defeat convinced Franz Joseph that national and social opposition to his government was too strong to be managed by decree from Vienna. Gradually he recognized the necessity of concessions toward Hungary, and Austria and Hungary thus moved toward a compromise. In 1866 the Prussians defeated the Austrians, further underscoring the weakness of the Habsburg Empire. Negotiations between the emperor and the Hungarian leaders were intensified and finally resulted in the Compromise of 1867, which created the Dual Monarchy of Austra-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The autonomous Transylvanian constitution

The autonomous Transylvanian constitution was reintroduced by the Diploma of October 1860. The desire to reunite Transylvania with Hungary lead to the compromise of 1867 and to the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, a real union under one monarch. Saxons, fearing of loosing their national rights, and Romanians, desiring an independent state, were not happy with this union.

Austria-Hungary

The Compromise of 1867, which created the Dual Monarchy, gave the Hungarian government more control of its domestic affairs than it had possessed at any time since the Battle of Mohacs (see fig. 4). However, the new government faced severe economic problems and the growing restiveness of ethnic minorities. World War I led to the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, and in the aftermath of the war, a series of governments--including a communist regime--assumed power in Buda and Pest (in 1872 the cities of Buda and Pest united to become Budapest).

![[Map of the counties of the Kingdom of Hungary]](kingdom_of_Hungary_counties.png)

Map of the counties of the Kingdom of Hungary

Once again a Habsburg emperor became king of Hungary, but the compromise strictly limited his power over the country's internal affairs, and the Hungarian government assumed control over its domestic affairs. The Hungarian government consisted of a prime minister and cabinet appointed by the emperor but responsible to a bicameral parliament elected by a narrow franchise. Joint Austro-Hungarian affairs were managed through "common" ministries of foreign affairs, defense, and finance. The respective ministers were responsible to delegations representing separate Austrian and Hungarian parliaments. Although the "common" ministry of defense administered the imperial and royal armies, the emperor acted as their commander in chief, and German remained the language of command in the military as a whole. The compromise designated that commercial and monetary policy, tariffs, the railroad, and indirect taxation were "common" concerns to be negotiated every ten years. The compromise also returned Transylvania, Vojvodina, and the military frontier to Hungary's jurisdiction.

At Franz Joseph's insistence, Hungary and Croatia reached a similar compromise in 1868, giving the Croats a special status in Hungary. The agreement granted the Croats autonomy over their internal affairs. The Croatian ban would now be nominated by the Hungarian prime minister and appointed by the king. Areas of "common" concern to Hungarians and Croats included finance, currency matters, commercial policy, the post office, and the railroad. Croatian became the official language of Croatia's government, and Croatian representatives discussing "common" affairs before the Hungarian diet were permitted to speak Croatian.

The Nationalities Law enacted in 1868 defined Hungary as a single nation comprising different nationalities whose members enjoyed equal rights in all areas except language. Although non-Hungarian languages could be used in local government, churches, and schools, Hungarian became the official language of the central government and universities. Many Hungarians thought the act too generous, while minority-group leaders rejected it as inadequate. Slovaks in northern Hungary, Romanians in Transylvania, and Serbs in Vojvodina all wanted more autonomy, and unrest followed the act's passage. The government took no further action concerning nationalities, and discontent fermented.

Anti-Semitism appeared in Hungary early in the century as a result of fear of economic competition. In 1840 a partial emancipation of the Jews allowed them to live anywhere except certain depressed mining cities. The Jewish Emancipation Act of 1868 gave Jews equality before the law and effectively eliminated all bars to their participation in the economy; nevertheless, informal barriers kept Jews from careers in politics and public life.

Rise of the Liberal Party

Franz Joseph appointed Gyula Andrássy--a member of Deák's party--prime minister in 1867. His government strongly favored the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and followed a laissez-faire economic policy. Guilds were abolished, workers were permitted to bargain for wages, and the government attempted to improve education and construct roads and railroads. Between 1850 and 1875, Hungary's farms prospered: grain prices were high, and exports tripled. But Hungary's economy accumulated capital too slowly, and the government relied heavily on foreign credits. In addition, the national and local bureaucracies began to grow immediately after the compromise became effective. Soon the cost of the bureaucracy outpaced the country's tax revenues, and the national debt soared. After an economic downturn in the mid-1870s, Deák's party succumbed to charges of financial mismanagement and scandal.

As a result of these economic problems, Kálmán Tisza's Liberal Party, created in 1875, gained power in 1875. Tisza assembled a bureaucratic political machine that maintained control through corruption and manipulation of a woefully unrepresentative electoral system. In addition, Tisza's government had to withstand both dissatisfied nationalities and Hungarians who thought Tisza too submissive to the Austrians. The Liberals argued that the Dual Monarchy improved Hungary's economic position and enhanced its influence in European politics.

Tisza's government raised taxes, balanced the budget within several years of coming to power, and completed large road, railroad, and waterway projects. Commerce and industry expanded quickly. After 1880 the government abandoned its laissez-faire economic policies and encouraged industry with loans, subsidies, government contracts, tax exemptions, and other measures. The number of Hungarians who earned their living in industry doubled to 24.2 percent of the population between 1890 and 1910, while the number dependent on agriculture dropped from 82 to 62 percent. However, the 1880s and 1890s were depression years for the peasantry. Rail and steamship transport gave North American farmers access to European markets, and Europe's grain prices fell by 50 percent. Large landowners fought the downturn by seeking trade protection and other political remedies; the lesser nobles, whose farms failed in great numbers, sought positions in the still-burgeoning bureaucracy. By contrast, the peasantry resorted to subsistence farming and worked as laborers to earn money.

Social Changes

Hungary's population rose from 13 million to 20 million between 1850 and 1910. After 1867 Hungary's feudal society gave way to a more complex society that included the magnates, lesser nobles, middle class, working class, and peasantry. However, the magnates continued to wield great influence through several conservative parties because of their massive wealth and dominant position in the upper chamber of the diet. They fought modernization and sought both closer ties with Vienna and a restoration of Hungary's traditional social structure and institutions, arguing that agriculture should remain the mission of the nobility. They won protection from the market by reestablishment of a system of entail and also pushed for restriction of middle-class profiteering and restoration of corporal punishment. The Roman Catholic Church was a major ally of the magnates.

Some lesser-noble landowners survived the agrarian depression of the late nineteenth century and continued farming. Many others turned to the bureaucracy or to the professions.

In the mid-1800s, Hungary's middle class consisted of a small number of German and Jewish merchants and workshop owners who employed a few craftsmen. By the turn of the century, however, the middle class had grown in size and complexity and had become predominantly Jewish. In fact, Jews created the modern economy that supported Tisza's bureaucratic machine. In return, Tisza not only denounced anti-Semitism but also used his political machine to check the growth of an anti-Semitic party. In 1896 his successors passed legislation securing the Jews' final emancipation. By 1910 about 900,000 Jews made up approximately 5 percent of the population and about 23 percent of Budapest's citizenry. Jews accounted for 54 percent of commercial business owners, 85 percent of financial institution directors and owners, and 62 percent of all employees in commerce.

The rise of a working class came naturally with industrial development. By 1900 Hungary's mines and industries employed nearly 1.2 million people, representing 13 percent of the population. The government favored low wages to keep Hungarian products competitive on foreign markets and to prevent impoverished peasants from flocking to the city to find work. The government recognized the right to strike in 1884, but labor came under strong political pressure. In 1890 the Social Democratic Party was established and secretly formed alliances with the trade unions. The party soon enlisted one-third of Budapest's workers. By 1900 the party and union rolls listed more than 200,000 hard-core members, making it the largest secular organization the country had ever known. The diet passed laws to improve the lives of industrial workers, including providing medical and accident insurance, but it refused to extend them voting rights, arguing that broadening the franchise would give too many non-Hungarians the vote and threaten Hungarian domination. After the Compromise of 1867, the Hungarian government also launched an education reform in an effort to create a skilled, literate labor force. As a result, the literacy rate had climbed to 80 percent by 1910. Literacy raised the expectations of workers in agriculture and industry and made them ripe for participation in movements for political and social change.

The plight of the peasantry worsened drastically during the depression at the end of the nineteenth century. The rural population grew, and the size of the peasants' farm plots shrank as land was divided up by successive generations. By 1900 almost half of the country's landowners were scratching out a living from plots too small to meet basic needs, and many farm workers had no land at all. Many peasants chose to emigrate, and their departure rate reached approximately 50,000 annually in the 1870s and about 200,000 annually by 1907. The peasantry's share of the population dropped from 72.5 percent in 1890 to 68.4 percent in 1900. The countryside also was characterized by unrest, to which the government reacted by sending in troops, banning all farm-labor organizations, and passing other repressive legislation.

In the late nineteenth century, the Liberal Party passed laws that enhanced the government's power at the expense of the Roman Catholic Church. The parliament won the right to veto clerical appointments, and it reduced the church's nearly total domination of Hungary's education institutions. Additional laws eliminated the church's authority over a number of civil matters and, in the process, introduced civil marriage and divorce procedures.

The Liberal Party also worked with some success to create a unified, Magyarized state. Ignoring the Nationalities Law, they enacted laws that required the Hungarian language to be used in local government and increased the number of school subjects taught in that language. After 1890 the government succeeded in Magyarizing educated Slovaks, Germans, Croats, and Romanians and co-opting them into the bureaucracy, thus robbing the minority nationalities of an educated elite. Most minorities never learned to speak Hungarian, but the education system made them aware of their political rights, and their discontent with Magyarization mounted. Bureaucratic pressures and heightened fears of territorial claims against Hungary after the creation of new nation-states in the Balkans forced Tisza to outlaw "national agitation" and to use electoral legerdemain to deprive the minorities of representation. Nevertheless, in 1901 Romanian and Slovak national parties emerged undaunted by incidents of electoral violence and police repression.

Political and Economic Life 1905-19

Tisza directed the Liberal government until 1890, and for fourteen years thereafter a number of Liberal prime ministers held office. Agricultural decline continued, and the bureaucracy could no longer absorb all of the pauperized lesser nobles and educated people who could not find work elsewhere. This group gave its political support to the Party of Independence and the Party of Forty-Eight, which became part of the "national" opposition that forced a coalition with the Liberals in 1905. The Party of Independence resigned itself to the existence of the Dual Monarchy and sought to enhance Hungary's position within it; the Party of Forty-Eight, however, deplored the Compromise of 1867, argued that Hungary remained an Austrian colony, and pushed for formation of a Hungarian national bank and an independent customs zone.

Franz Joseph refused to appoint members of the coalition to the government until they renounced their demands for concessions from Austria concerning the military. When the coalition finally gained power in 1906, the leaders retreated from their opposition to the compromise of 1867 and followed the Liberal Party's economic policies. Istvan Tisza--Kalman Tisza's son and prime minister from 1903 to 1905--formed the new Party of Work, which in 1910 won a large majority in the parliament. Tisza became prime minister for a second time in 1912 after labor strife erupted over an unsuccessful attempt to expand voting rights.

World War I

On June 28, 1914, a Bosnian Serb assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne. Within days Austria-Hungary presented Serbia with an ultimatum that made war inevitable. Prime Minister István Tisza initially opposed the ultimatum but changed his mind when Germany supported Austria-Hungary. By late August, all the great European powers were at war. Bands playing military music and patriotic demonstrators expecting a quick, easy victory took to Budapest's streets after the declaration of war. However, Hungary, was ill prepared for war. The country's armaments were obsolete, and its industries were not prepared for a war economy. By 1915 and 1916, Hungary sterted to feel the full impact of the war. Inflation ran rampant, wages were frozen, food shortages developed, and the government banned the export of grain even to Austria. Franz Joseph died in 1916, and Charles IV (1916-18) became Hungary's new king. Before being crowned, however, Charles insisted that voting rights be extended to a larger proportion of the Hungarian population. Tisza resigned in response. By 1917 the Hungarian government was slowly losing domestic control in the face of mounting popular dissatisfaction caused by the war. Of the 3.6 million soldiers Hungary sent to war, 2.1 million were wounded or killed. By late 1918, Hungary's farms and factories were producing only half of what they did in 1913, and the war-weary people had abandoned hope of victory.

On October 31, 1918, smouldering unrest developed into revolution in Budapest, and roving soldiers assassinated István Tisza. Pressured by the popular uprising and the refusal of Hungarian troops to quell the disturbances, King Charles was compelled to appoint the "Red Count" Mihály Károlyi, a pro-Entente liberal and leader of the Party of Independence, to the post of prime minister. Chrysanthemum-waving crowds poured into the streets shouting their approval. Károlyi formed a new cabinet, whose members were drawn from the new National Council, composed of representatives of the Party of Independence, the Social Democratic Party, and a group of radical bourgeois. After suing for a separate peace, the new government dissolved Parliament, declared Hungary to be an independent republic with Károlyi as provisional president, and proclaimed universal suffrage and the freedom of the press and assembly. The government launched preparations for land reform and promised elections, but neither goal was achieved. On November 13, 1918, Charles IV surrendered his powers as king of Hungary. However, he did not abdicate, a technicality that made a return to the throne possible.

The Károlyi government's measures failed to stem popular discontent, especially when the Entente powers began distributing slices of Hungary's traditional territory to Romania, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (colloquially Yugoslavia until the name became formal in 1929), and Czechoslovakia. The new government and its supporters had pinned their hopes for maintaining Hungary's territorial integrity on the abandonment of Austria and Germany, the securing of a separate peace, and exploiting Károlyi's close connections in France. The Entente, however, chose to consider Hungary a partner in the defeated Dual Monarchy and dashed the Hungarians' hopes with the delivery of successive diplomatic notes, each demanding the surrender of more land. On March 19, 1919, the French head of the Entente mission in Budapest handed Károlyi a note delineating final postwar boundaries, which were unacceptable to the Hungarians. Károlyi resigned and turned power over to a coalition of Social Democrats and communists, who promised that Soviet Russia would help Hungary to restore its original borders. Although the Social Democrats held a majority in the coalition, the communists led by Béla Kun immediately seized control and announced the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy fells apart - Hungary dissmembered by the Treaty of Trianon 1920

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy fell apart after the First World War. Despite Hungarian protest, the Romanian National Assembly proclaimed the joining of Transylvania to Romania, in the declaration of Alba Julia on December 1, 1918. The Allied and Associated Great Powers confirmed this and anexed Transylvania to Romania by the Treaty of Trianon, 1920 (June 4, 1920 in Versai, France), were Hungary was punished as none state in Europe before.

1920 Treaty of Trianon - Hungary torn apart

Unwillingly and under enormous pressure, on 4th July, the Hungarian delegation has been forced to signed the "Peace Treaty" which dismembered the 1000 years old country grounded by Saint Stephen (Szent István), the first hungarian King. 2/3 of Hungary's territory had been given to those surrounding countries, which actually occupied it.

The resulting "treaty" lost Hungary an unprecedented 2/3 of her territory, and 1/2 of her total population or 1/3 of her Hungarian-speaking population. Add to this the loss of up to 90% of vast natural resources, industry, railways, and other infrastructure.

The Paris Peace Treaty, "The Treaty of Trianon",(where the Hungarians were severely punished because being allied with the Germans in the war) not just dismembered Hungarythe central European state, (which has been the fortress and defender of Christianity for 500 hundred years against the invading Turks) but also made homeless 4.7 millions of Hungarians, which with the new borders were no longer the citizens of their own country, but the citizens of surrounding countries, which actually occupied it.

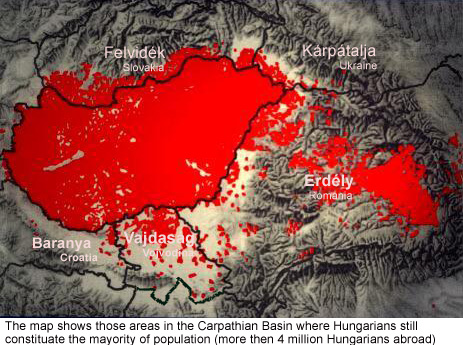

The map with inhabited area by the hungarians

Not even Germany, which lost only small amounts of territory, was "punished" to this extent. The Treaty of Trianon, by any objective account, was extremely harsh and unprecedented. It is the reason Hungarians today are the largest minority in Europe, numbering in the millions and, as the Helsinki Watch Committee wrote in 1989, "face discrimination, persecution, and destruction of their ethnic identity."

The rights on using their own language in schools, government institutions, news and media is or are severely limited or forbidden, the thousand years old cities and villages were (and still are) not allowed to ware their original Hungarian names on the road signs, all the property which has been confiscated from big land lords and the Catholic church, after the first & second World War, are still in state possession.

In lots of cases, the Hungarians still live in discrimination, just because they are Hungarians.

This was done to a nation whose borders were established over a thousand years earlier (896 A.D.) and one who lost countless lives defending the rest of Europe from numerous invasions from the Mongolian Tatars and the Ottoman Turks.

About 197,000 Transylvanian Hungarians fled to Hungary

About 197,000 Transylvanian Hungarians fled to Hungary between 1918 and 1922,[5] and a further group of 169,000 emigrated over the remainder of the interwar period. Among those who departed were destitute agricultural laborers, disheartened aristocrats, disillusioned intellectuals, workers and their families searching for better opportunities in Hungary or in some cases, overseas. In 1921, the Popular Hungarian Party and the National Hungarian Party were founded. In 1922 these political parties fused to form the Hungarian Party of Romania.

The new regime's objective became to effectively Romanianize Transylvania in a social-political fashion, after centuries of Hungarian rule. The regime's goal was to create a Romanian middle and upper class that would assume power in all fields. The Hungarian language was expunged from official life, and all place-names were Romanianized. In the land reform undertaken in 1921, Transylvanian aristocrats (most of them ethnic Hungarians or assimilated as Hungarians from other ethnic groups) were dispossessed of large landed properties, with the land being then given (in smaller plots) to peasants (the majority of whom were ethnic Romanians). This move, approved by Romania's King Ferdinand I, changed the ethnic distribution of land ownership.

Map of Romanian counties with Hungarian presence.

The Magyar population complained about the insufficiency of schools in their language and the pressure to send their children to Romanian-language schools. In the private economy, the dominant social position of Hungarian, Jewish and Saxon business people was somewhat eroded, as the Romanian government tried to improve the relative position of businesses owned by ethnic Romanians by adopting preferential, protective measures. Higher education was completely Romanianized, except for a chair of Hungarian Literature at the University of Cluj. On the other hand, the minority's cultural activities were barely obstructed by Romanian official policies.

World War II - atrocities committed by Romanians against hungarians in Transsylvania

In 1940, the joint German-Italian sponsored Second Vienna Award gave back Northern Transylvania to Hungary, which held it until 1944. The award was intended to partly compensate Hungary for the territories lost with the Trianon Treaty, and ensure its continued loyalty towards Germany and Italy. However, it was again simply a re-drawing of national borders in a multi-ethnic region, without providing a real solution. Historian Keith Hitchins summarizes the situation created by the award:

Far from settling matters, the Vienna Award had exacerbated relations between Romania and Hungary. It did not solve the nationality problem by separating all Magyars from all Romanians. Some 1,150,000 to 1,300,000 Romanians, or 48 per cent to over 50 per cent of the population of the ceded territory, depending upon whose statistics are used, remained north of the new frontier, while about 500,000 Magyars (other Hungarian estimates go as high as 800,000, Romanian as low as 363,000) continued to reside in the south.

During this period there were atrocities committed by Romanians in 1944 against the székely hungarians. Here under we are presenting testimonies from two chapters from the "White Book on Atrocities against Hungarians.

Part from THE WHITE BOOK

ATROCITIES AGAINST

HUNGARIANS

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1944

IN TRANSYLVANIA, ROMANIA = The complete book is available here.

Counties Csík and Háromszék in September-October 1944

"As it stood defenseless before the advancing Romanian and

Soviet troops, Háromszék became the most endangered area after

the turn in Bucharest on August 23, 1944. Hungarian and German

military leaders decided to give up the “sack-shaped” area of the

Székelyland, and to organize their defense along River Maros

(Mures), similarly to the situation of the Romanian invasion in

1916. Consequently, the military authorities ordered the evacuation

of the region in the first days of September 1944. Although the

order referred to the entire civilian population, mainly intellectuals

and the employees of public administration, education, justice and

healthcare left the region. Besides city dwellers, the village

intelligentsia (priests, teachers, notaries, etc.) left their homes as

well. Those who stayed on had to bear serious consequences. Only

in County Háromszék 6,000 families, approximately 30,000

persons were forced to leave their homes.1 (In most places the

majority of farmers hid in the surrounding mountains, woods,

sheep-pens or remote hamlets.) According to a report by Béla

Demeter, only 60,000 of the 170,000 inhabitants of County Csík

remained in their homes by the end of December 1944. Demeter

stated that people in Csík did not flee; they were simply driven away

by Hungarian and German soldiers. (Instead of 8,200, the entire

population of Csíkszereda and Zsögöd was 2,100 at the time.)2

Romanian-Soviet troops entered Sepsiszentgyörgy, the heart

of County Háromszék, on September 9, 1944. (Csíkszereda fell to

their hands two days later, on the 11th.) Except for a minor skirmish

between retreating German and advancing Romanian soldiers in the

neighborhood of Sepsiszentgyörgy, there were no serious fights in

the valley of River Olt during the first days of September. Returning

Romanian administration followed the advancing Romanian troops.

The confidential report of November 7, 19443, forwarded to the

Presidium of the Council of Ministers gave account on the state of

public administration. Prefect Victor Cerghi Pop and five of his

magistrates set up their office at Háromszék. Only 45 of the 65

notaries reported to work. The police and gendarme also returned.

The personnel of the appointed district education inspectorate

appeared in full number but teachers reported to work only in a

small number. Courts did not returned yet. Beside the Romanian

currency (lei) the Hungarian (pengo˝) one was still in circulation.

(Rate of exchange: 1:30.) Prefect Aurel Tetu also returned to Csík

with only four of his 5 magistrates, and 21 of 59 notaries presented

themselves. Neither education nor Court personnel returned. Most

of the Hungarian inhabitants of cities fled.

For the time being, Romanian administration could only

partially fulfill its tasks. Yet the report stated that as a result of the

energetic work of Prefect V. Cerghi Pop things are settling down at

a quick pace.4 What did it mean in practice? The Prefects tried to

settle occurring problems in the spirit of restitutio in integrum,

dictated by the instructions of government commissioner Ionel Pop.5

Hungarian signs were taken off everywhere. According to the

government commissioner’s decree, officials who held offices

before August 30 1940 were restored to their position and were

obliged to return to their posts. Hungarian schools established after

August 1940, many of them were opened in the same building

which were taken away from the Hungarians between 1920-1940,

were closed down or they were forcibly taken over by the returning

Romanian staff again. Instead of providing them protection against

the Maniu-guards, the returning gendarme often terrorized local

inhabitants. The arrival of Orthodox priests, who fled in September

1940 from Háromszék, in September 1944 caused serious

problems. They also continued in the spirit of restitutio in integrum

their forced conversion activity pursued between the two world

wars.

The letter7 written by the inhabitants of Bölön (Belin) of May

31, 1945 (already under Groza's government) give us an insight

view of the activity of the Romanian public administration.

According to the letter, Romanian troops entered the village on

September 2. Hungarian officials (who did not flee!) were

dismissed. The army brought a notary from the neighboring village,

Lüget, and János Kölcse (Ion Calcea?),who fled in 1940, was

appointed magistrate. The Romanian gendarme and the Romanian

villagers (Maniu-guard members, according to the letter) terrorized

Hungarian inhabitants. They were beaten, hand grenades were

thrown at two houses and the mother of the Calvinist minister was

badly beaten. Romanian gendarme arrested the members of the

Székely Frontier Guard Forces, but they were released by the

Soviets. Along with young factory workers, they were taken to

internment camps at Földvár, Tövis (Teius), Nagyenyed (Aiud) and Gyulafehérvár. Many prisoners died because of food shortage

during the winter. The measures were aimed at the physical

destruction of the Hungarian people. 8 These grievances could

have been written in many other villages as well. Local

survey on the activity of the Romanian public administration in

September-November 1944 could provide further important details.

We have to answer the question: What was the reason for the

bloody terror in Székelyland? The causes for atrocities were

quite varied. Almost anything from an old military bugle to an empty

grenade box and unloaded arms found in the attics without ammo,

was enough for the Maniu guardsmen to produce resistance fighters

and hiding Hungarian partisans under the pretext of hunting

for partisans. There would have been lesser reprisals if they had

really been hunting for partisans or for those who kept arms at

home illegally.

Another pretext was the revenge for the demolition or

damaging of Orthodox churches in Székelyland after the Second

Vienna Verdict, or the re-orthodoxization of believers who in

meantime returned to their original (Calvinist, Catholic) religions.

Many sources say that the volunteers in the autumn 1944,

and later the authorities of the Groza government after March

6,1945, considered the Székely Frontier Guard Forces,

operating under the command of the 2nd Transylvanian army, as an

irregular and volunteer units.10 Therefore Guardsmen looked

first of all for their members both at Szárazajta and at

Csíkszentdomokos (Sîndominic). (Though the search provided a

good opportunity for robbery and murder as well.)

The third reason was personal revenge. There are several

examples for it at Szárazajta, Csíkszentdomokos and Csíkdánfalva

(Danesti).

Anti-Hungarian Atrocities in Háromszék

According to eyewitnesses’ testimonies11, the volunteers,

under the command of Captain Gavril Olteanu, marched in

Sepsiszentgyörgy with ceremony on September 19, ten days after

the Romanian troops.12 The guardsmen, arriving from the direction

of Szotyor, quartered on the building of Mikó College. They thrown

the valuable books and furniture to the street. Their initial action

consisted of search for hidden arms, but it was a mere pretext for

robbery and looting. An appeal was published on September 20 in Desrobirea under the title of “Our Present and Prevailing Way”,

inviting their Transylvanian brothers to join. The article mentions

Iuliu Maniu as the founder of volunteer commandos: “The

Transylvanian volunteers of the Iuliu Maniu regiments have joined

the army to bring the hour of final victory closer. Some of them

have started for the final battle. (...) The others maintain law and

order in cooperation with the military authorities. (...) Transylvanian

Romanians! Let us regain our freedom by fire and blood. We will

destroy Hungarian prisons and we will chase Hungarian-German

hangmen out of towns and villages. We will take our cruel revenge

for the four-year occupation. Let Romanian firearms and bayonets

declare final sentence over the murderers of the Puszta [Hungarian

steppe]. (...) Transylvanian brothers! Gather under the banner

hoisted by Iuliu Maniu…”

The September 12th issue of the Desrobirea gave report on

the actions of the volunteers, stating that they continued to round up

terrorists from villages. Let us see some examples to show the real

nature of these actions. We, however, have to state it that these facts

are nothing but the tip of the iceberg...

It is written in the records of January 13, 1945 13 that

guardsmen raped István Kovács ' pregnant wife in Árkos (Arcus)

on September 22. According to the testimony made by Vilmos

Kisgyörgy14 Magistrate István Váncsa compiled a list of those who

had been members of the Székely National Defense Force. Most of

the 70 persons were finally released in exchange for cash or food,

but seven people condemned for anti-state activity were taken to the

prison in Sepsiszentgyörgy and then to the death camp of Földvár.

Árkos citizens say that those who called the guardsmen into the

village were driven by personal revenge. Although they have no

memory of István Kovacs, otherwise a Sepsiszentgyörgy-resident,

they still have vivid memories of the robberies and abuses

committed by Olteanu' s people: They took away everything they

could move, animals, cattle, poultry, everything. (V. K.)

According to a Desrobirea article, on September 23, a group

of 120 volunteers, led by M. Florea, went to the villages of

Gidófalva and Zoltán and in cooperation with local authorities,

they made adequate measures required by the situation.15 (my

italics) We have to read this report under certain reserves, as there

were 100-150 volunteers stationing in Sepsiszentgyörgy at the time.

It is highly improbable that the whole company moved to the two

villages. The Gidófalva people remember no guardsmen to visit their

village.16 The only thing they remember is the brutality and ravages

of the entering Soviet troops.

Under the title “Voluntarii ardeleni stârpesc ultimele resturi

de banditi. Crimele din comuna Pachia” (Volunteers annihilate the

last remains of the bandits. The crime of Páké.), the September 24

issue of Desrobirea writes about the revenge campaign of captain

Olteanu at Páké a couple of days after the volunteers arrived in

Sepsiszentgyörgy. Two Romanians were murdered that village,

Olteanu, accompanied by 50-60 volunteers went to Páké to revenge

it. According to the villagers, retiring German soldiers had probably

killed the two shepherds. Their hanged bodies were found on the

banks of River Feketeügy two days after the front had moved

away.17 The procedure at Páké was the same as in Szárazajta and

other villages: one inhabitant called the volunteers for reasons of

personal revenge. As a reprisal for the death of the two Romanians,

Olteanu arrested 100 Székely villagers to execute them without any

legal sentence. The innocent victims were lucky to have two Soviet

soldiers incidentally patrolling the village. Albert Illyés, one of the

accused, who had learnt Russian in a First World War prisoner's

camp, reported to the soldiers that they were to be illegally executed.

The Soviets ordered the Olteanu guardsmen at gunpoint to set the

Hungarian free. Not forgetting to pillage it first, Olteanu' s men had

left the village in the end.

There were no murders committed at Sepsiszentgyörgy, but

pillage and abuse was customary. According to the records of the

HPA, merchant Béla Lapikás was arrested and beaten, and his

warehouse was looted.18 Volunteers, wearing all kinds of uniforms,

Romanian, captured Hungarian and German ones or even civilian

clothes, had no official supplies. Consequently they lived on pillage

and robbery during all the way they were raving in Székelyland.

As the guardsmen was marching on northward along River

Olt, their appearance at Szárazajta, the remote Erdővidék village is

rather queer. To entirely conceive the matter, we have to go back to

the history of the settlement between the two world wars.

Szárazajta: Local Vengeance or Fight Against Partisans

Romanians have been living in the small village since the

18th century. Alike the farmer Székelys, the Romanians were

shepherds. As their trade was prosperous, they managed to buy

great amount of lands from impoverished Székely villagers from the

end of 19th century on. As a result of two centuries of co-existence

– except for their religion that remained Orthodox – a gradual change in language had started (without forced assimilation) (As

a 1930 Romanian census revealed, 1,649 Hungarian and only 16

Romanian inhabitants19 lived in Páké. The 1920 Transylvanian

census, using the method of name etymology, recorded 217

Romanians in the village.20 (301 villagers were Orthodox or Greek

Catholic in 1910.)

Re-romanising Hungarianised Romanians was one

of the main tasks of Romanian governments between the two world

wars. As one of its results was that during the 1921 land reform all

persons of Romanian names or of Orthodox or of Greek Catholic

denominations – who might not even speak Romanian at all –

received land, while many Székelys just as entitled to it did not.

Beside the unfair discrimination in land distribution, grazing was

another serious reason of conflicting interest. Between the two

world wars the Székelys often quarrels with Romanians shepherds

as they used to graze their sheep on the cultivated lands of the

former. In most cases the authorities supported the cause of the

majority Romanians.

After the two-decade Romanian rule, Northern

Transylvanian Hungarians/Székelys welcomed the entering

Hungarian troops. The Székely inhabitants of the village celebrated

the news of the Vienna Verdict with frantic joy – but not only joy

got into some of their heads. A few lads threw stones at the houses

of Romanians, but beside minor damages, nothing serious happen.

(In his declaration published by the end of the 80s, János Berszán

(Ioan Birsan), said to be the instigator of the Szárazajta events,

mentioned only shatters but not crimes nor torture en mass.21) But

after Hungarian gendarme showed up law and order was reestablished.

No atrocities occurred. The Orthodox priest of

Baráthely was the only one to leave the village with the retiring

Romanian administration after the Vienna Verdict. Those who were

forcibly converted to Orthodox religion between the two world

wars, returned to their ancestors’ churches, like in many other

Székely villages.22 In 1941, the Romanians were also called up [in

the Hungarian army]. They submitted themselves to military service

together with the Székelys. Although, the village was located close

to the Vienna border no Romanians fled for Southern (Romanian)

Transylvania.

After the breakaway on August 23, 1944, the frontline

quickly reached the village. Unfortunately local intellectuals,

including Calvinist minister Géza Kolumbán, teacher and parish

choir-master Viktor Incze, left the village when the evacuation order

came. The village was left without leaders. On September 2, a minor skirmish between the advancing Romanian troops

and the German rear-guards took place on the confines of the

village. As a result of an unexpected German tank counterattack

from the direction of Nagybacon (Ba˘t¸ani), the Romanians suffered

considerable losses. “Well, looking out of the cellar window, we

saw the retreating Romanian soldiers running into the village. Some

were wounded, or something else, in this or that statement, some

were undressed and other lost their caps. They were running

away.”23 Villagers gathered almost twenty corpses in the streets. In

meantime both the Romanians and the Germans retired. However,

the unexpected Romanian defeat had to be explained: The villagers

helped the Germans in one or another way, and for sure, they

murdered wounded Romanian soldiers. Szárazajta consequently was

a village of partisans and had to be severely punished.24

Eyewitnesses we have interviewed state – and the same was

reported by Albert Incze – that Tódor Bardoc (Teodor Barduti)

was the one who called the guardsmen into the village, when

he heard that they were stationing in Sepsiszentgyörgy. It is

supposed that Bardoc presented Olteanu a complete list.25 The

guardsmen appeared at Középajta on September 25, Monday

morning. No one was injured there, as Magistrate György M.

Váncsa (Gheorghe Vancea) told Olteanu: There is nobody guilty

here. Anyone who committed any crime has already taken to the

citadel in Brassó. 26 The decent local magistrate of

Romanian origin rescued the Székely population of

Középajta from the revenge of Olteanu and his

commando. (Although he himself had quite a good reason for

revenge as he was persecuted by Fascist bandits in the first days of

1940!27) Pretending to go for searching German soldiers, and

traveling on wagons confiscated in Középajta, the 30-35-strong

group of volunteers arrived in Szárazajta on the afternoon of the

25th. When we left the house – Tódor Bardoc lived in the next one –

I saw a group of men arriving They were dressed half civilian, half

military, and half Hungarian, half Romanian. A group, a platoon.

(B. N.) The guardsmen were quartered in the houses of Tódor

Bardoc, Simon Bogdán and other Romanian villagers. One of the

local lads, Gábor Domokos was also ordered to transport the

guardsmen from Középajta on his cart. According to his recorded

testimony, he saw the list in Olteanu’s hand. He even warned Gyula

Németh and his family, that their names were on the list, but they

did not believe him.28

Béla Gecse was the first victim. With the help of local Romanian guides, volunteers started to collect the people on the list

at the dawn of the 26th. Around half past four, a group of

guardsmen appeared at Gecse's house. When they “knocked” at the

door with the rifle butt,. Béla Gecse tried to escape, but one of the

guardsmen shot him dead. His name was recorded in the official

death register on October 16, 1944, with the note accidentat de

ra˘zboi (war accident!).29 But the death register of the Calvinist

Church has always recorded the real reason and it recorded this case

as execution by the Maniu-guard.

József Málnási was the second victim of the

massacre. During the 1945 trial of the guardsmen in Brassó, his

widow confessed the following: On September 26, Bogdan

Alexandru and a volunteer broke into their house. The volunteer30,

defendant Romoceanu – as she recognized him at the trial – fired at

her husband. He was taken to the schoolyard, where he died of his

wound. József Málnási also tried to escape. He was shot with an

explosive bullet in his thigh. The most horrible was that then this

man who was shot and who was wounded, was taken to the

schoolyard and exposed on a blanket in front of the other

Hungarians there. The poor man was begging right to the end for

somebody to give him a slip of water or shoot him dead! (S. I.)

At early dawn, the guardsmen and their Romanian guides

collected the unaware Székelys who were just preparing for work.

János Berszán and one of the volunteers picked up Izsák Németh.

He had a personal conflict with him, dating back to before the war

(when Németh once beaten Berszán for grazing his sheep on his

second crop). Simon Berszán took the guardsmen to Lajos

Elekes. Elekes was accused by Olteanu of firing at Romanian

soldiers from the bell tower of the Szárazajta Calvinist church.31

Viktor Bogdán and Ferdinánd Bardoc made Gyula Nagy and his

son, Gyula Nagy Jr. taken to the school hall, the “arrest room”

for the accused. (They were accused with firing at Romanian

soldiers from a German tank…) Dániel Nagy was lucky of being

informed on the arrival of the shady visitors by József Benko˝, a

coachman from Középajta, he managed to hide and escape. In the

morning hours, Simon Berszán made it announced by the village

drummer that all Hungarians aged between 16 and 60, had to gather

at the schoolyard. Those who would hide and not appear, were to be

shot dead.32 Hearing of the order, Albert Szép started off for the

schoolyard. But his wife, Regina Málnási, was taken there by

force, and accused her of cutting off the finger of a wounded

Romanian officer in order to take his ring. The Nagy brothers,

Sándor and András were dragged in the building of the kindergarten behind the school. (One of the sources states that 26

accused were gathered in the schoolyard.)33

5-600 Hungarians were surrounded by gunmen at the

schoolyard, with a machine-gun pointed at the frightened mass from

the roof of the building on the opposite side. The wounded József

Málnási and the body of Béla Gecse were taken there too. Captain

Olteanu read the accusation according to which the accused had

committed various crimes against the Romanian army. Then he

announced their death sentence. (No mercy for Hungarians!)34 Then

the guardsmen started a show of force to intimidate the Hungarians.

Ferenc Kálnoki, chairman of landowners' community of the

village, who due to his positions had many enemies among the

Romanians anyway, was laid on a stump and beaten half death with

a wet rope. He was followed by his son-in-law, Zoltán Incze,